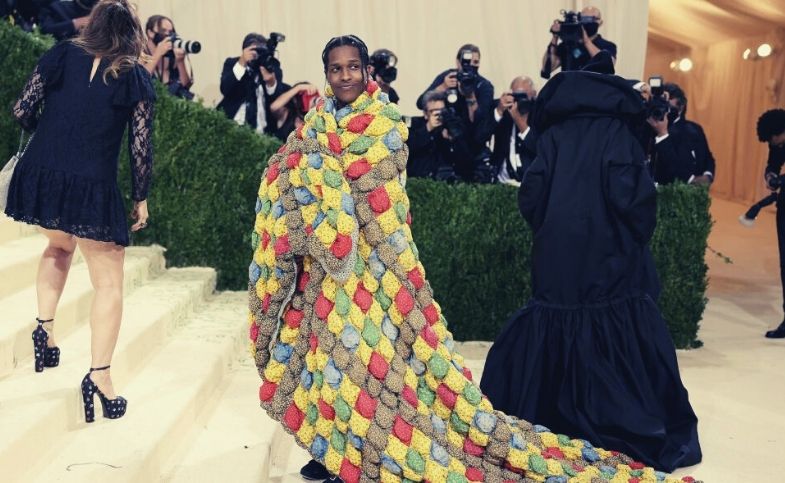

When A$AP Rocky arrived at the Met Gala in September, he did something few others could: he went toe-to-toe with Rihanna.

As is customary for his style icon partner, he was among the night’s best dressed. The rapper, on the other hand, stole the show with his own fashion statement: a gigantic, multi-colored quilt.

The piece was based on a blanket acquired in a California thrift store and was custom-made by designer Eli Russell Linnetz and quilter Zak Foster. A woman later identified the original quilt as one made by her great-grandmother and shared a photo of it on Instagram.

Quilts are being transformed from family heirlooms to luxury products, and their appearance at fashion’s biggest night was only the latest proof of the craft’s modern resurrection. As designers increasingly turn to reused materials as evidence of their environmental credentials, they’ve appeared on major runways and in nostalgia-laden winter collections.

Seeing quilts go popular excites long-time quilters like Mary Fons, former editor-in-chief of Quiltfolk magazine. “The fact is that quilts are cool. They’re timeless,” she wrote in an email “When you see them on red carpets it reinforces that, and as quilters, we’re here for it.”

New Americana

Though luxury companies such as Norma Kamali and Moschino have lately included quilted details to their collections, smaller labels such as Stan Los Angeles have adopted the technique as their own.

The surfwear lines of the California label incorporate a lot of upcycled quilts. One overshirt costs $2,250 and is constructed from a quilt made in Pennsylvania in 1870.

Tristan Detwiler, the brand’s founder, initially became interested in upcycling quilts when he turned an old baby quilt into a jacket, which he described as the first piece he had produced “from scratch” over video chat.

He later met quiltmaker Claire McKarns, who escorted him to her warehouse, where he saw “hundreds and hundreds of her hand-curated quilts,” as he put it. Detwiler was later invited to join her craft club, where she met more experienced quilters.

Detwiler’s creative approach is around the tale of specific textiles, but he also upcycles a range of other items passed down through the centuries, such as a sun-patterned coat hand-stitched by his own great-great-great-grandmother in the 1800s. His clothing are labeled with information about their backstories. “The energy of family and generations and history in that obviously activates emotion,” he remarked.

After two and a half years in business, the designer now focuses on one-of-a-kind pieces, two of which are on show at the Met Costume Institute’s “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion” exhibition. The show comprises a jacket-and-trouser set fashioned by Detwiler from a 19th-century quilt given to him by McKearns, and it explores the country’s fashion history.

It stands next to a Ralph Lauren patchwork ensemble fashioned from antique textiles in the 1980s, which is one of 12 quilted items in the exhibition.

“Adolfo did it in the late ’60s, Ralph Lauren did it in the ’80s, and then Calvin Klein and designers like Emily Bode started it up again around 2017.” Fons added, “every 30 years or so.”

Quilting For Generations

Quilting has a long history in America, with Fons defining it as a “democratic art” that has been done by individuals of various economic, racial, and religious origins. Regional styles evolved as well, from English-inspired mosaic quilts made by mostly White New England crafters to the brightly colored geometric designs of Gee’s Bend, Alabama, whose enslaved community quilted for “survival,” according to artist Michael C. Thorpe, who works with the medium, with women repurposing clothing and feed sacks to keep their families warm.

Rev. Jesse Jackson, a civil rights leader, used the metaphor “many patches, many pieces, many colors, many sizes, all woven and held together by a common thread” in a famous speech at the 1984 Democratic National Convention.

The phrase opens the Costume Institute exhibition, according to assistant curator Amanda Garfinkel, who says it corresponds to the theme of the display “emphasis on inclusivity and diversity. ” People “respond emotionally” to quilted exhibits, according to Garfinkel, because they “carry personal and historical narratives.”

“Of course, our country doesn’t always exhibit these values, but quilts are still seen as icons of maybe what we hope to be,” Fons said.

Artists like Thorpe are infusing other parts of design into their quilted pieces rather than looking to historical styles. Thorpe uses textile portraits to bring Black history, his own multiracial experiences, and childhood fantasies to life.

He recently partnered with Nike on quilts inspired by the NBA’s past and future. People at the artist’s recent Miami exhibition, despite his contemporary approach, brought up their own grandmothers when gazing at his work, he said.

He went on to say, “Quilting makes people feel. It’s like a familial knee-jerk reaction (ties). That, I believe, is what people are aiming towards.”

Pieces Interconnected

In reinventing fashion with ancient quilts, American designers may, ironically, be jeopardizing the craft, according to Fons. “We are in huge danger of losing great tracts of American history, particularly the history of women and marginalized communities, since these are the people who have made the most quilts over our nation’s history,” she added.

In reinventing fashion with ancient quilts, American designers may, ironically, be jeopardizing the craft, according to Fons. “We are in huge danger of losing great tracts of American history, particularly the history of women and marginalized communities, since these are the people who have made the most quilts over our nation’s history,” she added.

Hand-sewing skills are also becoming increasingly rare. Quilts are often constructed by hand or machine patchworking together pieces of fabric, then sandwiching a layer of batting between the decorative front pieces and fabric backs (giving them a distinctive puffiness and insulation for warmth).

While electric longarm sewing machines, which can sew on both the x and y axes, have revolutionized the industry in recent decades, some quilt artists and designers are now reintroducing “hand-piecing and hand-quilting” and “connecting with… quilt heritage again,” according to Fons.

Quilting’s resurgence, she suggested, could represent a yearning for “authenticity” in the face of fast fashion’s growing digitization and mass production. In contrast to the fast pace of contemporary living, the anonymity of industrial production, and the ephemerality of digital culture, Garfinkel emphasized “the sense of community and preservation associated with quilting, especially in contrast to the accelerated speed of contemporary life, the anonymity of industrial production and the ephemerality of digital culture.”

“I think people are now more interested in things that take a little bit longer, and enjoy reverting to craft… The idea of extremely slow (handcrafting) and something to do with a group,” Thorpe said, adding that people are feeling “severe fatigue from technology.”

A New Generation

Fons, who continues to serve as an editorial advisor for Quiltfolk, estimates that the magazine’s audience is “around 50 years,” but she has noticed an increase in interest among younger generations. She said she had spoken to both first-time quilters and individuals who “picked it back up during lockdown.”

Fons, who continues to serve as an editorial advisor for Quiltfolk, estimates that the magazine’s audience is “around 50 years,” but she has noticed an increase in interest among younger generations. She said she had spoken to both first-time quilters and individuals who “picked it back up during lockdown.”

Despite certain barriers to entry, such as the cost of machines, fabric, and batting to fill out quilts, DIY-minded TikTok members are leveraging their acquired abilities to save money on clothing. Wandy the Maker, for example, offers quilting instructions to inspire Gen Zers to think about their wardrobes more responsibly.

Others, like @samrhymeswithhamm, have had success on the platform with the hashtag #quilttok, with a video of her constructing a cactus-themed quilt receiving 2.4 million views.

Quilting’s popularity in America has a “element of fetishism,” according to Fons. “At its heart, the yearning for handmade things, artisanship, and ‘slow’ processes makes sense. Modern life moves really fast and can be kind of scary.”