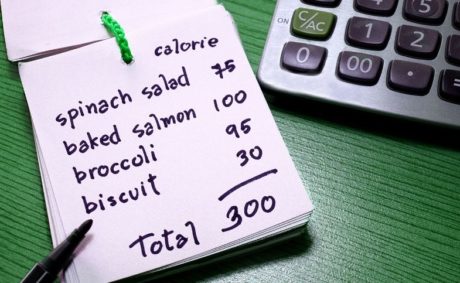

“Let me ask you a question: how many calories do you think the average woman should have each day?” asks Herman Pontzer, a Duke University evolutionary anthropology professor specializing in metabolism. For a little while, anyone asked will be taken aback. All of us trying to lose weight should be the one asking and, isn’t the answer obvious?

Clare Finney, F&M Food Writer of the Year 2019 say “2,000” cautiously. Pontzer says “No! Women burn around 2,400. Men, around 3,000. These figures are based on thousands of measurements, taken around the world. So when you look at calories on a label or menu and decide what you can eat based on an intake of 2,000, you’re starting with a made-up number. There’s no added information in knowing the calories.” To put it simply, when it comes to calculating calories, humans aren’t very good at it.

Is this, however, a sign that they shouldn’t bother? That is the challenge posed by the British government’snew rule requiring eateries and cafe’s with more than 250 employees to display their calories beginning in April. The rationale is straightforward: to assist consumers in making healthier choices and to encourage businesses to provide lower-calorie options. The reality, as always, is a little more complicated.

Let’s start with the facts: eating more calories than you burn causes you to gain weight. Obesity, which affects 64% of adults in the UK as of 2019, is a risk factor for a variety of diseases, and it costs the NHS billions of pounds every year. According to Herman, the measure gets one thing right: “Weight is affected by the calories you are eating, so there is sense in society focusing on calories. I like the idea that if people knew more, they would make good choices.” He goes on to say that the difficulty is that “there is no evidence that that is true.

In the United States, on the other hand, where calorie counts have been required on restaurant menus since 2018, obesity has gradually increased. In New York, it appeared that these menus pushed some customers to choose items with more calories, not fewer, either in an attempt to get more bang for their buck, or from a “screw it” mentality. “I don’t know why. I’m not a psychologist. But the idea that people are overeating just because they don’t know the calories? I’m really not sure,” Pontzer adds, referring to his new book, Burn, which is based on 20 years of rigorous research into what happens to the energy we consume.

“People are not going to be going into a burger restaurant and saying, I didn’t realize there were a massive number of calories in fried and side dishes,” says Anthony Warner, a former food industry development chef and author of The Angry Chef: Bad Science and the Truth About Healthy Eating. Similarly, knowing how many calories ar in a chocolate digestive does not prevent one from eating many more. Examining a half-empty packet later and confirm what I already knew, it’s a cause of regret – but when it came down to it, that knowledge didn’t influence one’s actions. “Already several of the big chain restaurants offer calorie labeling on their website or on their menus,” says Warner, “and I’ve not consistently seen evidence of benefit.”

There are numerous explanations for this. Obesity is a multifaceted, systemic problem that has more to do with economics, society, and the processing of particular foods than it does with human decision. “The things that will improve obesity will be lifting people up socially and economically, [and] addressing systemic problems, rather than making people feel guilty about calories,” Warner adds. Improving working conditions and paying employees more would in his opinion, be a far more successful method for huge restaurant chains to combat obesity.

The reason one eats another biscuit (and another) is partially personal, but it also highlights one of the larger issues that contribute to weight gain: some foods cause overeating. Food manufactured with additives or “industrial formulations” where flavor, sugar, fats, or chemical preservatives are added has been increasingly prominent in our diets over the last 70 years, and these foods are more or less meant to make us want more.

“The issue is not that you’re having an extra 500-calorie meal every day. Most people don’t do that. It’s consuming foods that trick our brains into overeating, which is more subconscious and a very slippery thing to get hold of,” Pontzer explains. We eat another biscuit because the biscuits are “flavor-engineered to be over-consumed,” as he puts it.

They don’t have a lot of filling fiber. They have a pleasnt texture, rich flavors, and are quick and inexpensive. In 2020, investigative food journalist and author Bee Wilson wrote in The Guardian, “We still don’t really know what it is about ultra-processed food that generates weight gain,” but “evidence now suggests that diets heavy in ultra-processed foods can cause overeating and obesity… regardless of sugar content.” It’s popular these days to blame sugar for everything, just as it was ten years ago to blame fat. However, as Wilson points out, singling out specific nutrients as harmful just causes ultra-processed food manufacturers to tweak their products to meet the trend, such as turning “low fat” items into “sugar free” versions and diverting attention away from the true villain.

“One day,” Pontzer quips, “it will be protein.” “It’s not beneficial to demonize specific nutrients. I’m not supporting sugar, but it’s not sugar that causes weight gain.” Excess calories do, but the chances of you overdoing it are small if you eat meals that aren’t excessively processed and high in fiber. “Eating too much broccoli will not make you fat. “I’m willing to put my career on the line for that allegation,” he chuckles. “It’s not flavor-engineered to be over-consumed, it’s low in calories, and it’s packed with plant proteins and fiber that fill you up.” He goes on to say that an entire bowl of broccoli has more calories than a single chip, but you’re not going to order a second or third bowl. Who in their right mind would stop at a single chip?

The problem with any single metric—sugar, fat, or calorie counts—is that it fails to account for the totality of a meal. Calorie counts are “such a crude weapon,” according to Thomasina Miers, co-founder of the Mexican restaurant Wahaca. “It makes no mention of fiber, despite the fact that it is the loss of fiber in our diets that is causing so many issues.” It makes no mention of nutritional value. It makes no mention of “carbon footprint,” which, while having no influence on weight growth, is not insignificant in the larger scheme of things. A diner at Wahaca would pass over their bean and feta tostada based on calories alone, but it’s also one of the most sustainable dishes on the menu, being “loaded in protein, fiber, and important minerals, and cooked using local [legumes].”

Former models Jemima Jones and Lucy Carr-Ellison manage Wild by Tart and Tart London, a restaurant and catering firm frequented by those in the fashion and arts as well as consumers smitten by their aubergine and cashew satay. Jones explains, “Cooking good but healthful meals is a significant component of what we do.” “Some restaurants could do a lot more to assist their clients in eating more mindfully. Many of us in the food sector, on the other hand, are already quite cognizant of what we’re offering. You can create delicious yet nutritious cuisine if you use locally and seasonally obtained foods instead of calorie counts.”

“In economics, there is a rule that once a measure becomes a target, it ceases to be a useful measure.” “By directly targeting calories, that metric loses its utility,” Warner explains. The goal of the government and the food business should be to “improve food, not only meet targets.” The latter simply leads to some businesses manipulating the system, such as serving the same size quantity of fries but advising them be shared between two individuals, or lowering calories by replacing fiber with drink. “It would be good if they lowered the calories by not taking out the fiber or cutting the protein,” Pontzer observes dryly, “but I don’t expect the food sector to act responsibly.” “They’re in the money-making industry.”

Another, less evident but more pernicious aspect of this calorie-counting obsession is that the persons most likely to pay attention to calorie counts are those for whom they are extremely unhelpful: those suffering from or recovering from eating disorders. As a past sufferer, I am all too aware of how stressful those small numbers can be. It’s depressing to think that eating out may be made even more unpleasant for the 1.25 million people in the UK who are already suffering from eating disorders. “Calorie counting can drive people with binge eating disorder to experience guilt and distress, and people with anorexia can become more concentrated on restricting their food intake,” says Tom Quinn, director of external communications at BEAT, England’s main eating disorder charity. There’s also no proof that adding calories to menus helps people lose weight.”

But it isn’t just people with eating disorders who will be harmed by this decision; it will affect the majority of us, because eating out is supposed to be a pleasurable experience above all things. People don’t come to Wahaca on a regular basis for a buttermilk chicken taco and a brownie, as Miers points out; they come “as a treat, two or three times a year.” Whether you’re a model, a middle-aged man with a dad bod, or somewhere in between, Warner insists that eating out should be about “building social ties, relaxing, and celebrating.” Is calorie counting ever beneficial? Sometimes, for certain folks. But there’s a lot more to eating than that.