Every spring, an inscription modest in size but crucial in importance appears at the bottom of the Met Gala invitations: the dress code. It was examined triviality in 2020 for “Camp: Notes on Fashion.” It was American Independence in 2021 for “In America: A Lexicon of Fashion.” On May 2022, it’ll be golden elegance and white-tie for “In America: An Anthology of Fashion.”

Yes, of course. Age of Innocence and The House of Mirth, both by Edith Wharton, should be reread. The participants of the 2022 Met Gala will be asked to reflect the grandeur—and possibly the dichotomy—of Gilded Age New York. From 1870 through 1890 (Mark Twain is credited with coining the term in 1873), the United States experienced unparalleled wealth, cultural transformation, and industrialisation, with skyscrapers and fortunes apparently appearing out of nowhere. Mrs. Astor and her 400 servants reigned polite society until the Vanderbilts pushed their way in.

The New York Times building and then the entire city were lit by Thomas Edison’s light bulb, which was patented in 1882. The 1876 telephone, invented by Alexander Graham Bell, made communication instantaneous and created a demand for operators to man the lines, ushering in one of the first big waves of women into the workforce. Wages in the United States have surpassed those in Europe (although, as Jacob Riis captured in How the Other Half Lives, far from everyone benefited).

Millions of immigrants entered the country via Ellis Island, where the newly erected Statue of Liberty welcomed them with a poem by Emma Lazarus (“Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free.”) Architects McKim, Mead, and White created Beaux Arts buildings all along Fifth Avenue, adding to the city’s beauty. In 1892, Vogue was formed with the goal of presenting the “world’s cultivated citizens’ point of view.” Cornelius Vanderbilt, Peter Cooper Hewitt, and John E. Parsons were among the first stockholders, and their surnames are still remembered in New York.

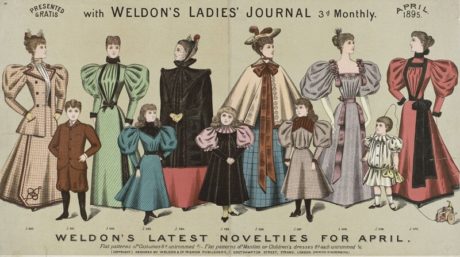

The colors were deep, rich jewel tones. Lighter hues were exclusively worn at home because they were impractical to wear when walking around New York’s streets. When going out, hats were a must, and they were frequently embellished with feathers. (In fact, the Audubon Society was created in 1895 in response to the millinery trade’s threat to birds.)

Corsets were widespread, and ladies adopted bustles to extend their backsides in the 1870s and 1880s – a frequent conceit was that a bustle should be large enough to hold an entire tea tray. However, by the 1890s, they had fallen out of favor, with mutton sleeves, bell-shaped skirts, and pompadour hairstyles taking their place.

This design was further popularized by illustrator Charles Dana Gibson, whose hourglass Gibson Girl pen-and-ink illustrations were widely used in magazines and commercials.

That isn’t to suggest that all Gilded Age attire was stiff and stuffy. Sportswear became an integral element of one’s clothing for the first time when leisure activities like biking and tennis grew popular among the well-heeled class. As demonstrated by John Singer Sargent’s 1897 photograph of Gilded Age socialite Edith Minturn, many ladies preferred a shirtwaist ensemble – or a long skirt paired with a feminine blouse – which allowed for easier movement.

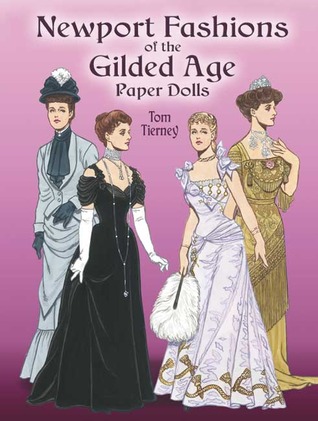

Parties, balls, and soirées, on the other hand, ushered in the most opulent style our country has ever seen. The opera, which was frequently attended by the upper echelon, had a stringent dress code: women wore tulle gowns with exposed décolletage, expensive fur-lined cloaks, and elbow-length gloves, and men wore top hats. The tuxedo made its debut in America in the 1880s (according to urban legend, a guy named James Potter wore the English-inspired suit style to a country-club event in Tuxedo Park, hence the suit’s name).

The most talented hostesses of the day threw outrageous costume parties with frenetic and fanciful clothes. Consider Alva K. Vanderbiolt’s opulent celebration for her daughter, Consuelo, in March 1883, which was dubbed “the most lavish celebration of the era.” The New York Times reported at the time that “the Vanderbilt ball has disturbed New York society more than any social even that has occurred here in long years.”

“Since the news of the event, which was made approximately a week before the start of Lent, there hasn’t been much else to talk about.” Guests lavished extravagant attention to detail – as well as large sums of money – on their outfits: Alice Claypoole Vanderbilt wore a white gown satin adorned with diamonds, a diamond headdress, and a light bulb as a jewelry accessory,

Mrs. Ada Smith, on the other hand, was dressed entirely in peacock feathers, from the train to the fan. Another guest wore a black-and-cream satin gown with gold stars embroidered on it, as well as a diamond necklace and hairpiece. It is no surprise that Tiffany, the Fifth Avenue fine-jewelry firm, flourished during this period.

When attendees gather at the historic museum on the first Monday in May in 2022, only time will tell how they interpret the dress code for the Met Gala. For those still debating their outfits, we’ll leave you with a quote from Edith Wharton’s The Age of Innocence, written about the endlessly ethereal Countess Olenska: ““Everything about her shimmered and glimmered softly, as if her dress had been woven out of candle-beams, and she carried her head high, like a pretty woman challenging a roomful of rivals.”