The demise of Roe v. Wade has drastically altered the lives of Black abortionists across the nation, with many medical and administrative professionals considering quitting their jobs out of concern for legal action.

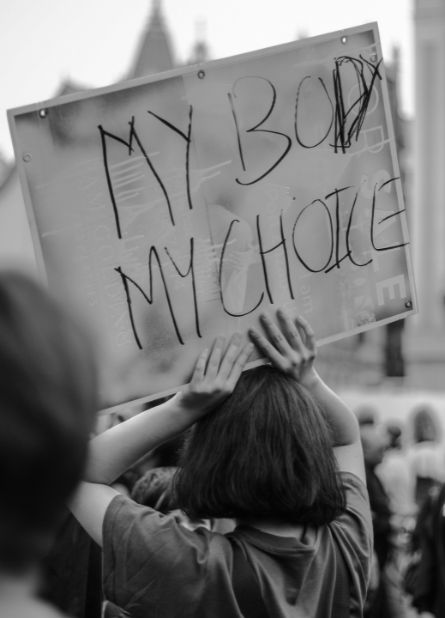

Black women-led clinics, grassroots organizations, and advocacy groups have traditionally filled gaps in the social safety net, and health care coverage, particularly in areas where access to abortion is restricted and patients are disproportionately Black and Latino. However, many Black abortion providers are concerned about their prospects due to legislation targeting doctors who perform the surgery and triggering laws meant to outlaw or restrict abortion. Some people are turning their attention to alternative reproductive healthcare.

Very frequently, folks ask, “If abortion is illegal will you comply?’ Dr. Sanithia Williams, a Black woman who performs abortions at Huntsville’s Alabama Women’s Wellness Center, says, “Yes, I will comply,’”

“I don’t agree with it and I don’t want to, but I don’t take for granted that I’m still a Black woman in Alabama. If the state is going to go after someone, I don’t hesitate to think that it will be somebody like me.”

Williams relocated in Alabama in 2019 after offering abortion services in California, Missouri, and Mississippi. She acknowledged that she may now have to retire from her position as one of the nation’s few Black women abortion providers.

“It feels like, to me, that I won’t be able to offer abortion anymore because I live in Alabama, and it will no longer be legal. So do I stay or do I go?” she added.

There are extremely few Black abortionists in the US, according to doctors like Williams, but there is no credible information on the demographics of these practitioners. Reproductive justice activists and abortion providers claim they have been preparing for a Roe reversal for years and strategizing how to satisfy people’s needs without constitutional protection.

Researchers, family planning experts, and advocates for reproductive justice have long noted the disparate effects that the loss of abortion rights and access will have on Black and Latino people in the South, who seek abortion care at higher rates and have less access to family planning services, leading to poor health, education, and economic outcomes.

As a result, Whole Woman’s Health’s Marva Sadler, the director of clinical services, admitted that she dreaded telling the workers at the clinic’s four locations on Friday about the ban. Whole Woman’s Health is one of Texas’ few abortion clinics.

Sadler said, adding that the locations may serve up to 30 patients daily, “I had to make those very difficult calls to each of our Texas clinics to ask them to … stop seeing patients immediately.”

But on Tuesday, a judge in Harris County issued a restraining order blocking an abortion prohibition in Texas that predated Roe, allowing some facilities in the state to begin offering abortion care temporarily. The delay only lasts until Texas’ trigger legislation, which virtually prohibits abortion, takes effect 30 days after the Roe ruling.

Sadler claimed that despite preparing for the ban since a preliminary draft of the decision surfaced in May, she hasn’t had time to think about her own future and isn’t sure if she’ll stay in Texas.

“I’m still trying to figure out what’s next for patients who we had to turn away. I hope to stay, I don’t have immediate plans to leave, but I do have a career, and I have to take care of my family. So I don’t know what happens next,” Sadler said, adding that she wants to work to get patients to Whole Women’s Health clinics in other states to receive care.

“No longer am I able to make sure I’m providing the perfect space right here at home, now I have to shift my focus on how to get these women to where they need to be.”

Before the restraining order on Tuesday, Sadler claimed that she had instructed the clinics to stop performing abortions right away out of concern for the severity of the consequences. Sadler lamented, “We’re not talking about fines. We’re talking about two to five years in prison for people who perform and help a woman perform an abortion. To protect our patients and our staff, we had to cease operations immediately.”

Not just South-based abortion clinics are getting ready for life after Roe. According to San Francisco-based physician Dr. Katherine Brown, patients have begun traveling from increasingly distant locations as abortion rights have come under threat. She expressed her optimism that she and her other healthcare professionals would be able to meet these patients’ demands and predicted that many wouldn’t have the means to go far for treatment.

Although California protects abortion rights, Brown expressed concern for the providers in states with outright bans or substantial limitations.

Brown, who collaborates with the Women’s Options Center and the University of California, San Francisco’s Center for Pregnancy Options, said: “Just as patients who are people of color are more likely to be prosecuted or their pregnancies more likely to be criminalized, a lot of us worry that abortion providers of color are also more likely to be criminalized as well.”

Brown has researched the significance of Black abortion providers in her roles as a doctor and researcher. Brown investigated the experiences and needs of 23 Black women who had abortions through a series of interviews. One woman emphasized the help of a Black physician.

The unnamed woman credited her doctor with assisting her with making this decision. “She helped me through this decision. She sat with me. She listened to me. I cried, she held, I mean, she physically held me. She never inserted her opinion. Even though I wouldn’t have minded if she did, she didn’t. She just listened and listened. I think they should clone her.”

Williams in Alabama is aware of the effects of Black suppliers. Williams stated that throughout medical school, many Black people and people of color were mostly being served by white men. She said she became an abortion provider and studied “birth work” to serve Black people. She remarked, “I’ve come to realize that there is something powerful about having a provider who looks like you.”

Williams noted that while patients from “all walks of life” are seen at the Huntsville center, Black or Latino individuals make up the majority. She claimed that three days a week, she and the other healthcare professionals do surgeries and frequently encounter demonstrators outside the clinic. The center will no longer provide abortion services, thus the demonstrators now have reason to rejoice.

Williams responded that the answer is not straightforward when asked if she will start traveling again to provide abortion services.

“I’ve done travel work before. But my husband’s family is from Alabama, our child is here. Travel work is not easy work. In the same way it’s unrealistic to expect that all of those people will get their health care elsewhere, it’s also unrealistic to think that all the abortion providers in the country are going to start doing travel work. Travel work is not the answer necessarily, and it’s not easy. It’s hard. And I’d be giving up time with my community. So it’s not a black-and-white issue.”